Political strategy in Singapore, pt. 1

How sound political strategy allows the opposition to perform in elections, pt. 1

Something I spend a lot of time thinking about is the importance of strategy. In Singapore, we don’t comment much on political strategy for many reasons. Firstly, our politics is dominated by the PAP, and as such, there is often much less room for broad political strategy in the first place. Additionally, the dearth of thoughtful op-eds thanks to the sorry state of our media means that this topic doesn’t come up very often.

I would like for political strategy to be unimportant. After all, elections should be decided on the grounds of policy and persuasion, and less by logistics, campaign finance, advertising, and the like. But as with most things regarding human behaviour, humans do not behave perfectly rationally, and there is a limit on how much information the average person takes in. As such, deploying a political party’s resources with a coherent strategy will be key for political success.

As an example, let’s briefly examine the strategy employed by the opposition in the 1991 election, as led by Chiam See Tong, then heading the SDP. In essence, the plan was for the opposition to contest just under half of all seats in Parliament, resulting in the PAP being on Nomination Day. The hope was to capitalize on the “by-election effect”, so-named because voters in by-elections don’t need to worry about their vote ousting the government, and thus often favour the opposition more than standard elections. The goal was to achieve such an effect on an entire general election by ensuring that voters know the PAP will be forming government before ballots have even been cast. Voters are thus free to vote for the opposition if they so choose, without risking any “freak elections” where the opposition unexpectedly come to power.

And it worked, with a then-unprecedented four seats being won by the opposition, the largest number up until that point since the 1963 election. The SDP picked up 2 additional seats bringing them to a seat total of 3, and the WP picked up Hougang SMC as well. A resounding success for the “by-election effect” strategy.

As a more modern example, take the WP’s own “East Coast Plan”, which they implemented in the era of Low Thia Khiang and continues to this day.

I will first note that I’m unsure whether the strategy I describe here has been formally implemented by the WP. While I will go on to assume that they have, there is still the possibility that what I observe is simply a coincidence.

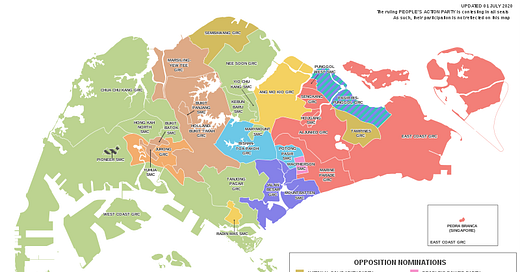

What I have dubbed the WP’s “East Coast Plan” stems from the following: if you look at in which seats the WP contests elections, you will note that the vast majority, if not all, of the seats contested by the WP since the early 2000s are in the Eastern half of Singapore.

Furthermore, many of the wards that the WP have won are clustered around each other. For instance, Low Thia Khiang’s ward of Hougang SMC is adjacent to Aljunied GRC, famously won by the Worker’s Party in the general election of 2011. Of course, flanking it to the north is Sengkang GRC, which the WP team led by He Ting Ru managed to win in GE2020.

Several explanations are possible for these geographic observations. For instance, perhaps these are coincidentally areas of historical strength for the WP. The WP has fielded teams for these areas for many general elections. Perhaps the demographics of the East make the people there generally more receptive to opposition thinking.

I suspect, however, this goes beyond mere coincidence. I believe that the WP are deliberately focusing their resources on the East to circumvent the electoral damage that gerrymandering of districts could inflict.

First, a brief explanation of gerrymandering. In short, it’s the practice of drawing electoral boundaries to favour one political party over another. One main idea behind gerrymandering is the idea of “cracking” - diluting the strength of opposing political parties by dividing their support among different constituencies. This prevents them from getting sufficient support in any ward to get elected, as their support is diffused over multiple wards.

While gerrymandering is hard to conclusively prove, there are many indications that gerrymandering is potentially occurring in Singapore. But we can make some educated guesses. If we were to hypothesize that cracking was occurring in the general election, we would expect to see that areas of opposition strength are either split apart or brought into a larger GRC which the PAP controls soundly.

With that in mind, let’s look at the electoral performance of the 2015 general elections, and the boundary changes in GE2020. Here are the constituencies which had the best opposition performance in 2015 (aside from those that they won) were, along with what happened to them in GE2020:

Punggol East SMC (48.2%), absorbed into the newly-created Sengkang GRC

Fengshan SMC (42.5%), absorbed into East Coast GRC

East Coast GRC (39.3%), absorbed Fengshan SMC

Sengkang West SMC (37.9%), split between Ang Mo Kio GRC and Sengkang GRC

Anecdotally, I have also heard from friends who live near the border between Tampines GRC and East Coast GRC, who note how they rarely vote in the same constituency two elections in a row. Clearly, the boundaries shift a fair bit from election to election, seemingly for the PAP’s political convenience. We can thus see how there is some indication that gerrymandering could be happening.

But now it makes sense why the WP would want to maintain a position of political strength spanning an entire section of Singapore. If the WP are in a position of relative strength for the entirety of Eastern Singapore, it becomes much less likely that redrawn electoral boundaries will have a vast effect. As an example, the options available for redrawing Punggol East SMC were to:

expand Pasir Ris-Punggol GRC or Ang Mo Kio GRC even more (though in the 2015 GE, both were already the maximum size with 6 seats),

join it with Aljunied GRC and essentially hand the opposition a free seat on a silver platter, or

to join portions of Pasir Ris-Punggol GRC with that to dilute the vote share, creating a new GRC in the process.

It seems that something along the lines of the latter was done, resulting in the formation of Sengkang GRC. The problem here was that due to geographic proximity, the other neighbouring Sengkang West SMC, which also saw strong WP performance, had to be included in the final GRC. As a result, there would still be a substantial amount of WP strength in the new GRC, and ultimately the WP managed to pull out narrowly ahead.

The story of Fengshan SMC is similar. Being nearly entirely surrounded by East Coast GRC, there is almost no choice but for the SMC to be absorbed by East Coast GRC if losing it is to be avoided. However, both are locations where the WP was doing okay!

Such is the power of the regional grip over the East that the Worker’s Party enjoys, and they are now reaping the political rewards for their foresight. It would fit this framing of the “East Coast Plan” if the WP begin to make moves towards Tampines GRC or Pasir Ris-Punggol GRC in the next few elections to truly consolidate their Eastern parliamentary stranglehold.

Having seen what the WP did using the “by-election effect”, let us now look at the political fortunes of the SDP.

The SDP split apart after Chiam See Tong had major disagreements with the SDP CEC and stepped away to form the Singapore People’s Party before the 1997 general election. The SDP lost much of their political strength as an opposition party after that, having not managed to win a seat since. Not to forget that Chee Soon Juan was sued for defamation by both Goh Chok Tong and Lee Kwan Yew following some comments he made in the 2001 general election. He was declared bankrupt in 2006, preventing him from re-entering the political arena until his bankruptcy was finally annulled in November 2012.

In GE2020, the SDP came up just short in Bukit Batok SMC (45.2% of the popular vote), where Chee Soon Juan was running, and in Bukit Panjang SMC (46.3% of the popular vote), where party chairman Paul Tambyah. Just after East Coast GRC, these two wards were the best performing opposition wards that the PAP still managed to hold on to.

Besides that, however, their electoral performance was rather poor. The SDP team in Holland-Bukit Timah GRC was soundly crushed by Foreign Affairs Minister Vivian Balakrishnan’s team, managing just 33.6% of the popular vote. The Marsiling-Yew Tee team fared no better against then-Minister for National Development Lawrence Wong, with 36.8% of the popular vote. Not to mention Yuhua SMC, where Minister of Culture, Community and Youth Grace Fu trounced the SDP’s Robin Low, who only earned 29.5% of the vote.

While not all of this can be blamed on the SDP, given the popularity of the Ministers they were running against, it can’t be the full reason. After all, this is comparable to Josephine Teo’s performance in Jalan Besar GRC, where the Peoples Voice led by Lim Tean earned 34.6% of the vote. This is already after she made her comments about migrant workers demanding an apology, making this both an indictment of the SDP and the Peoples Voice.

Quick aside: why does the name Peoples Voice not have an apostrophe???

Anyway, despite their improved electoral performance in GE2020, it is clear that the SDP are far from their Chiam See Tong glory days. Support for the SDP seemingly rests on the popularity of Chee Soon Juan and Paul Tambyah moreso than their policies.

So, how can the SDP move forward and grow their support? I propose that they will need a radical change in political strategy, and may only reap the benefits a decade or more away. More on the existing direction of the SDP, and what I propose as alternatives, next week!

Fun little electoral history tidbit: Wikipedia notes that, leading up to the 1997 general election, Chee Soon Juan got into a back-and-forth exchange in the Straits Times with PAP MP Matthias Yao about the lack of democracy in Singapore. Chee Soon Juan then challenged Matthias to stand against him in an SMC at the next GE. Thus, at Yao’s request, PM Goh Chok Tong agreed to separate Yao’s MacPherson ward from the rest of Marine Parade GRC such that the two could run against each other. Chee Soon Juan lost quite handily, but that’s not really the point. I just think it’s interesting to note how electoral boundaries were drawn up with the express purpose of letting this electoral duel take place between the two men. And yet, we are supposed to believe that electoral boundaries are drawn up impartially based on population changes. Hmm…

Stay tuned for more on the SDP next week!

~ Kai